I often feel I’m standing at the edge of the Universe, yelling into a tiny megaphone. My words fly out . . . no echo answers back, and it makes me wonder.

But sometimes, there is a response.

In January 2020 I posted a piece under the heading “A Most Unusual Day.”

(The post had no relation to the Jimmy McHigh-Harold Adamson song introduced by Jane Powell in the 1948 film A Date With Judy and later swung in a hip version by June Christy and the Stan Kenton Orchestra. I merely stole the song’s title to characterize a particular day in the life of my uncle, Edward F. Sommers, a pilot for Pan American Airways.)

On December 7, 1941, Uncle Ed was enroute to Honolulu from San Francisco, flying as first officer on Pan Am’s Anzac Clipper. That Sunday morning, radio signals made it clear Pearl Harbor was under attack. Captain Harry Lanier Turner changed course and landed at Hilo, two hundred miles away.

My rambling January 2020 post told about Uncle Ed’s experience that day and in the days following. I also mentioned the near-simultaneous attacks on several Pan Am stations in the western Pacific.

The post drew several Facebook comments and one on-page comment at the time of its posting. Then three and a half years passed.

Mac’s Comment

Suddenly, three weeks ago, a long comment was posted on the page by Mac McMorrow, a lifelong resident of Hawaii’s Big Island. In the late 1930s, dengue fever and bubonic plague were common in the Hawaiian islands. As a result, McMorrow’s father, the first graduate of MIT’s public health engineer program, was hired to suppress the disease-prone rat population near Hilo.

Though Mac McMorrow was a two-year-old toddler in 1941, Honoluolu Star-Advertiser columnist Bob Sigall reached out to him recently to comment on a note from one Alvin Yee. Yee had written:

“On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941 an unscheduled Pan Am Clipper flying boat [the Anzac Clipper my Uncle Ed copiloted] landed in Hilo Bay after eluding the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and [Mac McMorrow’s] father tried to go on board and inspect everyone for disease but some haughty State Department official wouldn’t allow it saying the passengers were VIPs.

“I happen to know the passengers included the young Shah of Iran and the Premier of Burma and their travelling parties on their way back to Asia. . . . Check with Mac to see if I got this story straight.”

McMorrow, in his reply to Sigall, stated: “I can’t confirm very much of his story based on what was passed down to me by my father. I doubt it was my father who was confronted by the State Department official. I think my father would have mentioned that kind of incident to me. My father was the senior Territorial Health Officer on Hawaii Island and he would have had the plane quarantined if the regulations were not followed.”

He then adds a tantalizing tale:

[W]hat I remember my father telling me was that a passenger on the plane was a US diplomat. He had to return to the mainland on the Clipper. However, accompanying him was an attractive Asian/Eurasian woman who was not an American citizen. She was not allowed to return on the flight. She was left in Hilo when the Clipper took off the next day. One of our handsome family friends quickly took her under his “protection”. He escorted her around Hilo for several days until she could get to Honolulu. You can imagine the gossip little Hilo would have enjoyed, even under martial law.

Gracious Reader, this is the first whisper of this attractive Asian/Eurasian woman to reach Your New Favorite Writer’s ears. Or eyes, actually. It’s downright titillating.

Idle Speculations

One can easily imagine a diplomat traveling sub rosa with an attractive woman to whom he was not officially attached—even in the innocent 1940s. In fact, if we were enjoying a novel or a screenplay, you could count on it. A living informant telling us he heard it as fact from his father certainly adds credibility.

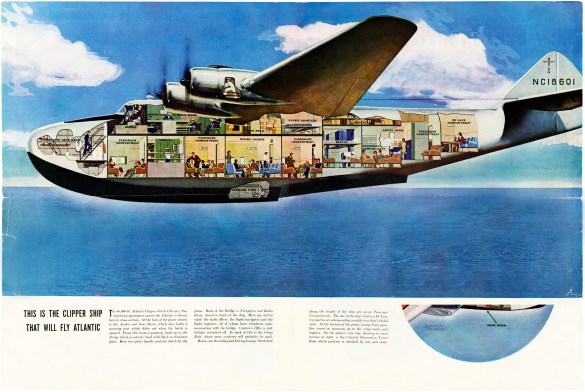

As to Alvin Yee’s assertion that “the young Shah of Iran [Mohammed Reza Pahlavi] and the Premier of Burma” were passengers on the plane: That’s not far-fetched, since the Boeing 314 Clippers were the ultimate form of transportation at the time, a natural choice for the rich, famous, and powerful. But the only other place I have seen this specific claim was in a 2016 article by Korea Times writer Nam Sang-so. I have emailed Mr. Nam a couple of times to find out where he got his assertion, but thus far have received no response.

This leaves me wondering whether Alvin Yee’s information came from Nam Sang-so’s article or from some other source.

Robert Daley, in An American Saga: Juan Trippe and his Pan Am Empire, says, “The Clipper [was to] be refueled here at Hilo and flown back to San Francisco as soon as possible. Passengers were welcome to ride back [or else] they could stay here and make their own way to Honolulu or Mauir or wherever they were going.” He says all the passengers opted to stay in Hawaii but makes no claim that any of them were VIPs. He mentions no Iranian royalty, Burmese politicians, or mystery women. But a lack of evidence that they existed is not necessarily evidence they did not exist, if you see what I mean.

So for now these things must remain intriguing mysteries.

Thanks, Mac

But I do thank Mac McMorrow, now evidently a very active 84-year-old, for adding to the mystery.

Even more, I thank him for honoring one of my posts by responding. You, too, Fair Reader, are welcome to add your comments to this or any other post on my “Reflections” blog. Or you may email me with comments. My address is larryfsommers@gmail.com.

Safe and happy travels to you all—whether by flying boat, magic carpet, or pickup truck.

Blessings,

Larry F. Sommers

Your New Favorite Writer